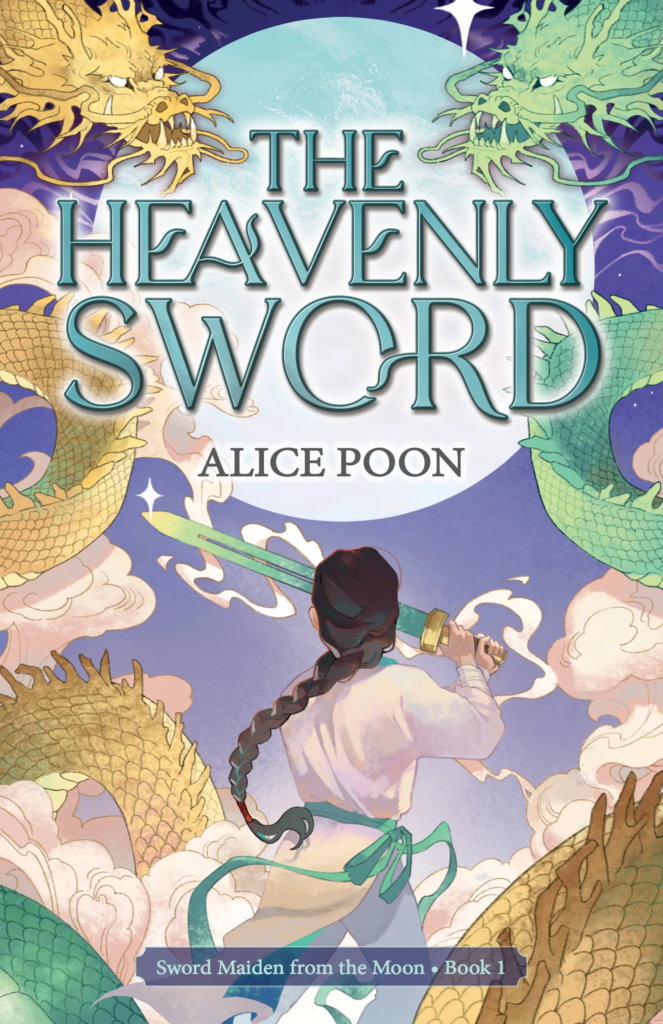

The Heavenly Sword is a very important book to me. When I was first looking for publishers who would be interested in an Urban Fantasy story set in Hong Kong, I began by looking through the companies that had published the nonfiction texts which I’d used as research. When I went to the website of Earnshaw Books, one such publisher, I saw, prominently displayed on the site’s front page, The Heavenly Sword. The synopsis promised fantastic adventure with an historic backdrop, in the tradition of wuxia greats like Jin Yong. And because of its inclusion in the Earnshaw Books catalog, I was able to pluck up my courage, contact the publisher, and proceed on my current journey with Project Shenmue.

More than that though, Alice Poon, the author, despite being a successful author and in a position that seems like a dream to me, is polite and sociable on social media. She has taken the time to answer questions I’ve posed to her on Twitter, given me likes and comments on my own platforms, and even was kind enough to mail me some bookmarks with characters from The Heavenly Sword. Thanks to her, I have made a contact in the writer realm, and she has been nothing but kind and encouraging to me.

Because of all this, I really wanted to like this book. To not like this book would be a sort of critical parricide, and, leaving her writing completely aside, Alice Poon seems like a genuinely cool person, whom I would love to get to know more and perhaps even become proper friends with in the future. So I can’t simply write The Heavenly Sword off and leave it at that, especially since I know that Poon herself will almost certainly read this review.

However, there are issues with this book that ultimately dragged down the experience for me, and I would not be able to write an honest review if I did not address them. My policy with criticism has always been that, so long as I do not personally insult the creator or the fans, anything goes. But, even though I know “constructive criticism” has become a BS buzzword like “just asking questions” or “devil’s advocate”, for this review, I will endeavor to frame every criticism I have in the most constructive way I can. This one is gonna be light on jokes, folks.

So, first of all, let me start with what is easily The Heavenly Sword’s greatest strength: its action sequences. When Poon writes action, the prose really comes alive, and despite her never using conjunctions between sentences (like “She drew her sword. Then she swung it.”), there is still an unmistakable flow to things. It’s a very rapid-fire, bam-bam-bam type of action, where everything happens in quick succession, and there’s never a wasted word. I always perked up and sat on the edge of my seat when reading a fight scene, and couldn’t wait for them to show up again, once they were over.

Unfortunately, less time is spent on action than on dialogue, and that is The Heavenly Sword’s greatest weakness. I’m sorry, but this dialogue is on par with Tyler Perry, especially since, like Perry, a lot of it consists of a new character showing up and directly telling us what they’re all about and what their deal is. “Show, don’t tell” is a cliché, but it’s also something which Sword could really use more of.

There are two bigger issues with the dialogue though, which ultimately bog the book down and make conversations a chore to read. The first one is pacing. Conversation, just like action, has a flow to it, a rhythm, a meter. And the bam-bam-bam style used for action doesn’t work as well for dialogue, because it makes conversations feel stilted and awkward. Now, obviously, something like Star Wars is infamous for its ropey dialogue, and for being much beloved despite all this. However, Star Wars is a story defined by constant, forward motion. There is always something happening, we are always moving, and the runtime at 2 hours is just short enough that the movie doesn’t overstay its welcome.

The Heavenly Sword though, while not a doorstopper on par with Brandon Sanderson, is still pretty hefty. And despite this heftiness, not that much actually happens in it. Or, rather, enough happens to justify a 200-something pagecount, but not the 300-something pagecount that Sword is, which leads to things feeling slow-paced and stretched out. If Poon had tightened the story up, whittled it down by a hundred pages or so, I think this would have been a much stronger book. But as it is, the pacing doesn’t quite work.

With writing, as with acting, there are lots of different schools and methods that people use. And I don’t really think one particular method is any better than another. But I want to bring up a certain method to illustrate a point. The scene-sequel method of writing tells a story through a collection of scene-sequel links. The scene is the action, the plot that moves the story along and forces the characters to reassess their situation. And the sequel is the reaction, the characters reassessing and processing things, and undergoing character development. The benefits of this structure is that it allows breathing space between the action, and motion between character introspection, creating a good balance between the two. And, obviously this structure doesn’t have to be rigid, but a good policy for writing is that, after you have the action, you have your characters’ introspective reaction to it.

The Heavenly Sword doesn’t really have its characters react to things. Either they roll with events with little to no reaction, or their reactions are only shown with a line or two of dialogue before things move on. It’s like, if someone receives a disturbing revelation, instead of taking a paragraph or so to have them demonstrate being deeply disturbed, they’ll simply say “I’m deeply disturbed!” and then continue about their business without much pause. This all creates a situation where the characters seem unusually deadpan, and it causes scenes that are meant to be emotional and impactful seem mundane and wooden.

With my second big criticism concerning the dialogue, I should note that Alice Poon has far more knowledge on the broader, literary tradition that she’s emulating than I do. While I’ve read bits of Jin Yong and Victorian translations of Chinese classics, my main exposure to the wuxia genre comes from films, like Little Dragon Maiden or Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain. As such, I realize that my next criticism may be an ignorant one to make, since it is operating under a different framework from a different literary background. However, if you’ll all bear with me, I think that The Heavenly Sword suffers from dialogue and prose being too Poughkeepsie.

What do I mean by this? Okay, so, in “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie”, Ursula K. le Guin writes about how many of the greats in fantasy fiction, like Eddison, Dunsany, Tolkien, etc., wrote in a distinctly fantastic, “Elfland” style, while later authors who were inspired by them all too often wrote in a more mundane, “Poughkeepsie” style. Her criticism was not that purple prose is better than plain prose though. Rather, because the residents of Elfland are not concerned with things like tax forms or powerpoint presentations, having them talk in the same way as us modern folk who are concerned with such things is an easy way to bring the reader out of the story. Whether by having characters use slang, metaphors, or sayings that are too modern, or that are too archaic (what Tolkien called “tushery”), this disunity in prose brings us out of the story.

The conversations of The Heavenly Sword are replete with this disunity in prose. And, I should make clear, I am guilty of this to some degree as well. If you go and read The Song of Morien, you’ll find characters who use more modern dialogue interacting with characters who speak in a more archaic manner. And even Tolkien himself was not immune to this disunity, with his dragon passing like an express train. However, with Morien, I made sure at least to have each character speak consistently. Morien never slips into Jacobean prose, and the ancient beings he encounters never use modern vernacular. In The Heavenly Sword though, characters all speak in the same mishmash of old and new, which makes it difficult to distinguish them through their dialogue, and which keeps tripping up the rhythm of their speech.

Whether it’s a wizened elder using terms like “kung fu buddies”, or characters going “Umm” like they’re valley girls, this disunity in prose causes none of the conversations to have the same vitality and life that is present in the action sequences. And again, maybe the distinction between Elfland and Poughkeepsie prose isn’t an issue in Chinese-language wuxia books. Maybe Jin Yong used this same mishmash of old and new in his own prose. Maybe I am simply being ignorant when I criticize Sword for these qualities. But Chinese and English are two very different languages, with their own strengths and weaknesses, and their own qualities that make them beautiful.

The thing is, while I’ve spent most of this review complaining about the expression of The Heavenly Sword’s story, readers may notice that I haven’t once mentioned anything about the idea behind the story itself. And that’s because, despite not being able to vibe with the expression, I actually really love the idea. Like, the story outline is great! If it weren’t for the dialogue taking me out of things, I think I would love it. I suppose the inherent sexism of the Taoist magic we see is kind of a bummer, but that’s really only a quibble, and the only quibble I have on that front. The only serious issues I had with The Heavenly Sword are its dialogue and pacing, and while those are foundational issues with this text, there’s definitely the germ of a really great story in this book.

So, Alice, if you stuck with this review up to this point, thank you for doing so. I know that it probably wasn’t easy (we writers are very fragile people, I know), and you may be tempted to write me off as a nasty critic who just doesn’t get it. But I hope that I was never condescending or ignorant in my criticisms, and also that you won’t block me on Twitter for this (or pull a Jim Bernheimer in the comments section).

Edit: Okay, so, Alice Poon (who, God bless her, took this review as well as anyone could) got in touch to let me know that, yes, the prose issues that I had with The Heavenly Sword are merely a reflection of how writing styles differ between the Chinese wuxia and the English fantasy traditions. So my second big criticism was ignorant! This does rather raise the question of, if you were to write a book with wuxia plot tropes but English prose style, it would cease to be a wuxia or not, but as interesting a question as that is, it’s probably worth exploring in a separate article. So, basically, if you are a fan of wuxia and the prose is not an issue for you like it was for me, I would highly recommend it. Unlike other wuxia novels I’ve encountered, Poon is able to keep things focused on a small ensemble cast, instead of branching off into a tangled web of characters that are difficult to keep track of. I think perhaps that the wuxia prose is simply an acquired taste, which I have not acquired yet.

Leave a Reply