Wait.

Wait.

WAIT!

IT WAS A JOKE!!!

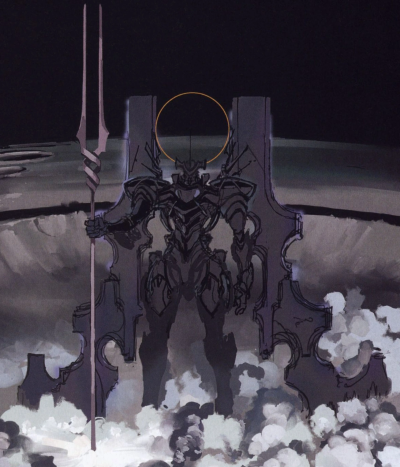

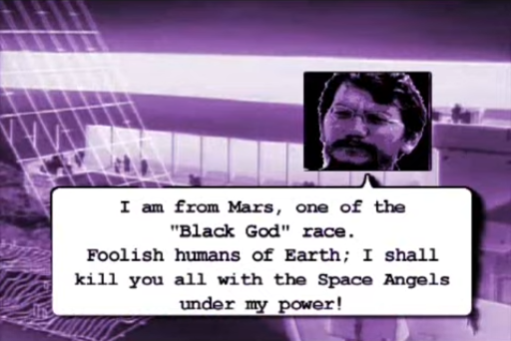

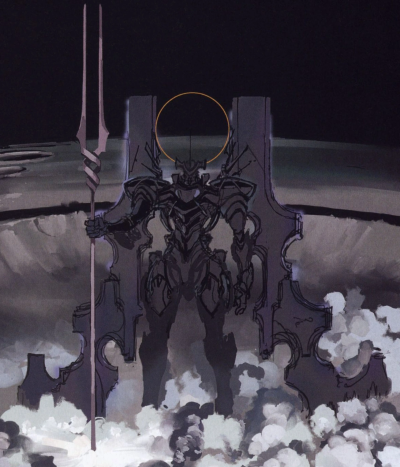

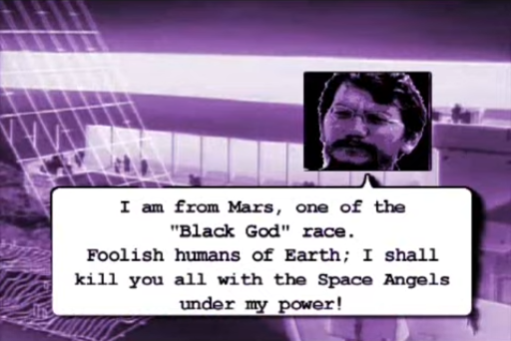

It was supposed to be a joke about the sort of idiotic enemy a studio would foist upon the production staff if they forced a second season of NGE! You weren’t supposed to actually do it! NOOOOOOOOOOOOO!!!

Wait.

Wait.

WAIT!

IT WAS A JOKE!!!

It was supposed to be a joke about the sort of idiotic enemy a studio would foist upon the production staff if they forced a second season of NGE! You weren’t supposed to actually do it! NOOOOOOOOOOOOO!!!

Okay, so…

Originally, this article was supposed to cover the video game adaptations of NGE. It made sense as a next step, since SEGA helped bankroll the original anime’s production on the condition that it had first dibs on the game rights to the Evangelion IP, and the first video game (also the first spinoff) of the series, Neon Genesis Evangelion: First Impression, came out in the middle of the show’s broadcast.

There’s just one problem: the game isn’t available in English. In fact, most of the Eva games are not available in English. I was able to find the two Girlfriend of Steel games and the Shinji Ikari Raising Project in English, but even with that small sample size I discovered an issue, namely that video games are a much greater time investment than shows or books. Yes, I know, that should have been obvious to me, but I am, alas, not a gamer, and I quickly realized that even investing time in these three games would cause the gap between my third and fourth articles in this series to swell like the Ultimate Warrior, unless I half-assed it and shat out a review of games I barely touched.

The popular image of a creator is that of Howard Roark, a lone genius who strives against those who would stifle or misinterpret his creative vision, such as fatuous editors who demand cuts or snobbish critics who only say mean things out of envy. And if there are other people involved in the production of Roark’s work, they are merely puppets carrying out his vision, their own talent judged by how much they dilute or distill the creator’s genius.

This is, of course, nonsense. Even in something like prose fiction, perhaps the least collaborative media, there are still publishers, proof-readers, and other people who help the writer come up with the final story we see on the page. And as for something like filmmaking, there are so many different moving parts in the process that it’s impossible to credit the final product to any single person, even if the screenwriter or director help steer the ship in a cohesive direction.

This is also to say nothing of how stories and art survive, not by being told, but by being retold and reworked with each passing generation. This is why the griots scoff at the idea of books, and why even the biggest King Arthur fan won’t defend the notion that the Icelanders are a slave race fit only to lick their English masters’ boots (even though that’s very much a part of early Arthurian stories). Even within the same generation, adaptations from one medium to another often involve different creators with different perspectives on the subject matter. That’s why Jack Torrence goes from a sympathetic character to a more villainous one in the film adaptation of The Shining. That’s why people fondly remember M.A.S.H. as a heartfelt tv drama and not a wildly sexist book. And that’s why I’m interested in checking out the manga version of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Hey everyone. So, if you were there for my Youtube channel, you probably know that I divide the books in the Discworld series into distinct eras. Because I never finished my Fantastic Fiction series on Discworld though, I never got a chance to fully explain just where I draw the lines dividing these eras, and what distinguishes them all from each other. Now that I’ve got this blog though, I’d like to take the time to do just that.

I call this the Genesis Era simply because it is, well, the genesis of Discworld, and of Terry Pratchett as an author. It’s where Sir Terry cut his teeth as a writer and laid the groundwork for the world he would explore. For the most part, these books are harmless fluff and fun romps, and are a far cry from the richer, deeper works Pratchett would later put out. However, even if, as Neil Gaiman says, the first batch of Discworld books are largely just a collection of jokes (and not even very good jokes), there are definitely the seeds of something great that you can see in them. Indeed, two of the books from this era (Wyrd Sisters and Guards! Guards!) display an unusual amount of richness and social commentary (Guards! Guards! in particular), heralding future heights the series would attain. And even with this as the series’s low point, I don’t think I would call any of the books here bad per se, just occasionally dull. So, while some people might tell you to skip to later books if you want to enjoy Discworld, I’d encourage readers to at least try out the Genesis Era books first, only skipping to the later stuff if you’re just not feeling it.

I call this the Golden Era because it represented a fresh surge of creativity in the Discworld series, as Sir Terry, now a far better, more experienced writer, shifted focus away from simple parodies and towards deeper satire, which is what made the series such a mainstay in the fantasy community. It represents a high water mark for the series as a whole, and while some might argue over where that mark ends, for me the last Golden Era Discworld book is Jingo, because it’s the last book in this bunch to feel truly innovative. Every book in the Golden Era feels like Pterry is excitedly buzzing with new ideas and new interests he wants to explore, and having now settled on a stable cast of characters, Pratchett uses this time to explore and enrich them further. This is where my favorite Discworld books are, and where a lot of fans recommend you start, since it’s early enough in the series that everything is still new, but late enough that Sir Terry is firing on all creative cylinders.

All good things must come to an end, and every car eventually runs out of juice. By the time the Discworld series numbered in the 20s, Pratchett had settled into a pattern. The books never became bad, since by that point even in his sleep Pterry could spin a good yarn. But there’s a distinct feeling of Sir Terry going through the motions by this point. The books in this era tend to either be proper, lasting sendoffs (The Lost Continent), experiments that don’t really work (Carpe Jugulum), more of the same (The Fifth Elephant), or onanistic canon-wielding (Thief of Time). Even the most interesting and creative of the books in this era, The Last Hero, feels like a tryout for new cover artist Phil Kidby. Again, it’s never bad per se, but at this point my (and I suspect Pterry’s) enthusiasm for Discworld was beginning to wane.

When you’ve been doing something for long enough, you can forget the things you liked about it. Even your favorite dish starts to taste stale if you eat it every day, and it’s only when some new thing comes along to shake up your routine that you remember why you fell in love in the first place. With Pratchett, that thing was The Amazing Maurice, an assignment to write a typical Discworld book, but for a younger audience (with all the considerations that entails). This ended up being a shock to the system, which allowed Sir Terry to explore new stories, new characters, and new corners of the Disc, resulting in his absolute best work. Night Watch is regarded by many, myself included, as the best Discworld novel, and it’s from this era, alongside other amazing classics like The Wee Free Men and Going Postal (amongst the most well-known Discworld books). Unfortunately, this was not to last.

In 2007, Terry Pratchett was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. This led to a reevaluation of his life and work, and a focus on public advocacy and charity work towards Alzheimer’s research. During this time, Pterry took a brief break from Discworld to publish his manifesto, Nation, and when at last he returned to the Disc, there was a noticeable change in mood. This last batch of books has a somberness and melancholy to it, no doubt informed by Prathett’s desire to make the most of whatever time he had left. And while he had given his characters sendoffs before, in this era it feels like Sir Terry is trying to give everyone a happy ending. Terry Pratchett succeeded in something that few authors accomplish, creating a fully realized fantasy world. And even as the characters he illustrated this world through reach the end of their stories in this era, the roots he put down are strong enough that you know the world will survive long after the characters, and Terry, are gone. GNU.

My goal with Project Shenmue is fairly straightforward: create a tribute to the Shenmue game series’ story, but with an emotionally satisfying conclusion and less racism. Seems simple enough, but I’m approaching the subject of China as a complete outsider. I know some basic history and have seen some films, but there’s still a lot I don’t know, and I want to at least put some level of research into whatever representation I give my story. Not because I’m hoping to earn some SJW brownie points, I don’t think Project Shenmue will even reach the eyes of the arbiters of woke, but really just for my own, personal satisfaction and artistic pride. I don’t have any great goals beyond telling a pulpy adventure story with less racism than the pulpy adventure stories that inspired it. But I hope at least that I can make something better than Bullet Train or Shogun (stories I… have very strong opinions about). To that end, I have set about getting my hands on whatever decent research texts I can find on the subjects I want to incorporate into Project Shenmue, which leads us to the topic of today’s article.

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén